The 2014 Syrian Presidential Election

One of the hoariest myths about the Syrian regime is that Bashar al-Assad has a democratic mandate as President of Syria, based upon the 2014 Presidential election.

I have regularly provided corrections to this claim over the years, but its recent repetition by the Director of Edinburgh University’s “Just World Institute” Tim Hayward has prompted me, to assemble into one place all the evidence that refutes this claim.

The background

Hafiz al-Assad seized power in a military coup directed against a rival faction of the Syrian Arab Baath party in November 1970. He enacted a new constitution in 1973 and in accordance with its terms a referendum, with no alternative candidate was held in the same year – to ratify his nomination as President., in which he secured 99.7% of the vote. He repeated this exercise regularly at 7-year intervals, increasing his vote to 100% (apart from 376 brave dissidents) by 1985. Hafiz Assad had planned for is his elder son Bassel, to succeed him as President after his death, but, as is often the case with the offspring of autocrats, Bassel developed a fondness for fast cars, and died in a crash in 1994. When Hafiz died in 2000, after some factional jockeying in the Baath Party, it was decided to put forward his younger son, Bashar. That required a hasty revision of the Syrian constitution, since Bashar was only 34 years old and the constitution stipulated that a candidate for the presidency had to be 40. Bashar also had to be fast-tracked through the Syrian army so that he could be accorded a senior rank that would give him credibility with the military before he took office.

Bashar went through the same “election” ritual as his father in 2000 gaining a slightly more modest 94.6% of the vote.

In 2012 Assad undertook a limited programme of constitutional reform, largely cosmetic in character, in response to the political unrest in the country This removed section 8 of the 1973 Constitution which assigned a special role to the Baath Party as “the leading party in society and the state, and laid down a framework for multi-candidate Presidential elections. Syrian businessman Wafic Said arranged for prominent British constitutional lawyer Sir Jeffrey Jowell to provide him with advice on this project However Jowell’s input to the final constitutional package seems to have been limited to a one -hour meeting with Assad in Damascus. In any event a new constitution was drafted and submitted to a referendum. This provided the framework for the 2014 Presidential election

The Constitutional framework

The Syrian Constitution, of 2012 specifies that” the religion of the President is Islam” (art.3) and lays down the following additional conditions for someone to be a candidate in the presidential election: He must

- Have completed forty years of age (reversing the amendment that allowed Bashar to stand in 2000)

- Be of Syrian nationality by birth, of parents who are of Syrian nationality by birth;

- Enjoy civil and political rights and not convicted of a dishonourable felony, even if he was reinstated;

- Not be married to a non-Syrian wife.

No real oppositionist could have met those criteria: With the liquidation of the brief “Damascus spring” from 2001 onwards, most prominent opposition figures were arrested and imprisoned under the security laws. By 2014 no critic of the regime could possibly have remained in the country for 10 years and avoided a conviction

But as additional insurance the Constitution requires that candidates must be nominated by 35 members of the Syrian Parliament. Given the domination of Syrian political life at all levels by the Baath party (whose head is Bashar al-Assad) that meant that any budding Presidential aspirant required the approval of the person they were hoping to stand against.

As a consequence only two people were approved to stand against Bashar al-Assad – Hassan al-Nouri and Maher Hajjar – both of them virtual unknowns. Al Nouri had held a junior role in the government under Assad and Hajjar was previously an MP for the regime-aligned People’s Will Party (although he parted ways with them because they opposed the election taking place).

If we add to that the fact that Assad had the full resources of the state at his disposal, that the government and Baath party have a virtual monopoly on the mass media, and that Syrian elections are overseen by the Supreme Constitutional Court, appointed by Assad, then it is obvious that there was no possibility of this being a free and fair election.

Views from the Ground

Some sense of what the elections looked like on the ground can be gained from the comments made by some of the election observers from the pro-regime, US based “Syria Solidarity Movement”. They were hosted by the regime in various locations and while they fulsomely endorsed the election and its outcome, some of them were a bit disturbed by some things they witnessed and shared their reservations in the Group’s online forum:

The election was not without its flaws. Members of the regional governorate parliaments accompanied the observer teams wherever we went, and we were treated as VIPs, which made the observation difficult. Voting was often done in the open whether or not private voting booths were available, and they often were not. Thanks to the presence of the members of regional parliaments, we had no difficulty interviewing the voters. By contrast, when some of us went unaccompanied to a polling station at our hotel, we found no volunteers willing to be interviewed.

Our hosts were overzealous. In one instance, we were given an opportunity to interview supporters of opposition candidates wearing opposition campaign t-shirts. Unfortunately, they knew nothing about the views of those candidates or the programs that they represent. They both described their jobs as “casual laborer”, meaning that they are available for hire.

There was no need to put on a show for our benefit. The occasion spoke for itself. Clearly, Syrians welcomed the opportunity to show support for their President, whose administration has demonstrated competence and strength, and has provided for its people under very trying circumstances. ….

Having said that, a voter wishing to send a message of dissent or protest by using her vote to reduce the margin of victory could easily have been intimidated by the atmosphere at some of the polling stations as well as the frequent lack of private voting booths (or the fact that few people were using them).

Journalist Sam Dagher, who was in Damascus for the election, reported that soldiers in uniform and members of the National Defence force militia turned out in demonstrations in support of Assad (although they were not allowed to vote under Syrian electoral law, which also prohibits the use of public resources by candidates). On election day itself some polling stations he visited were staffed by plainclothes military and security personnel; one actually had a banner bearing Assad’s image draped across its façade. He also witnessed cases of people casting multiple votes on behalf of family members.

Dagher also described a banner hung across the Damascus central market with a photo of Assad in military uniform and the slogan “God has created you to be the president of the Syrian Arab Republic” I bet neither of the opposition candidates tried to match that.

Deconstructing the Results

The official result of the election reported by the Supreme Constitutional Court was as follows.

Out of an electorate of 15.8 million, 11.6 million voted in the election (73.4% turnout); of these 10.3 million voted for Bashar Al-Assad (88.7%)

-

Some Political Arithmetic

In fact such an outcome is totally implausible: a little elementary arithmetic shows that the largest possible figure for the Syrian electorate in 2014 was 9.0 million more than a million fewer than the number of votes attributed to Assad.

9.0 million

Largest possible number of eligible voters in regime controlled Syria in 2014

11.6 million

Number of votes reported to have been cast in the 2014 election

10.3 million

Number of Votes reported to have been cast for Bashar al-Assad

If you are happy to take my word on this calculation then you can skip to section 2 below. If you want to see the details then read on.

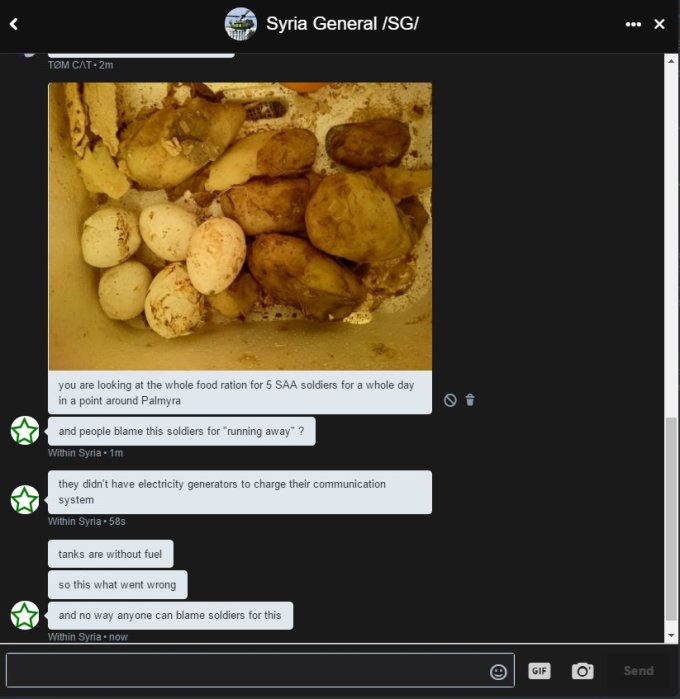

An insiders view of the Palmyra debacle on Twitter

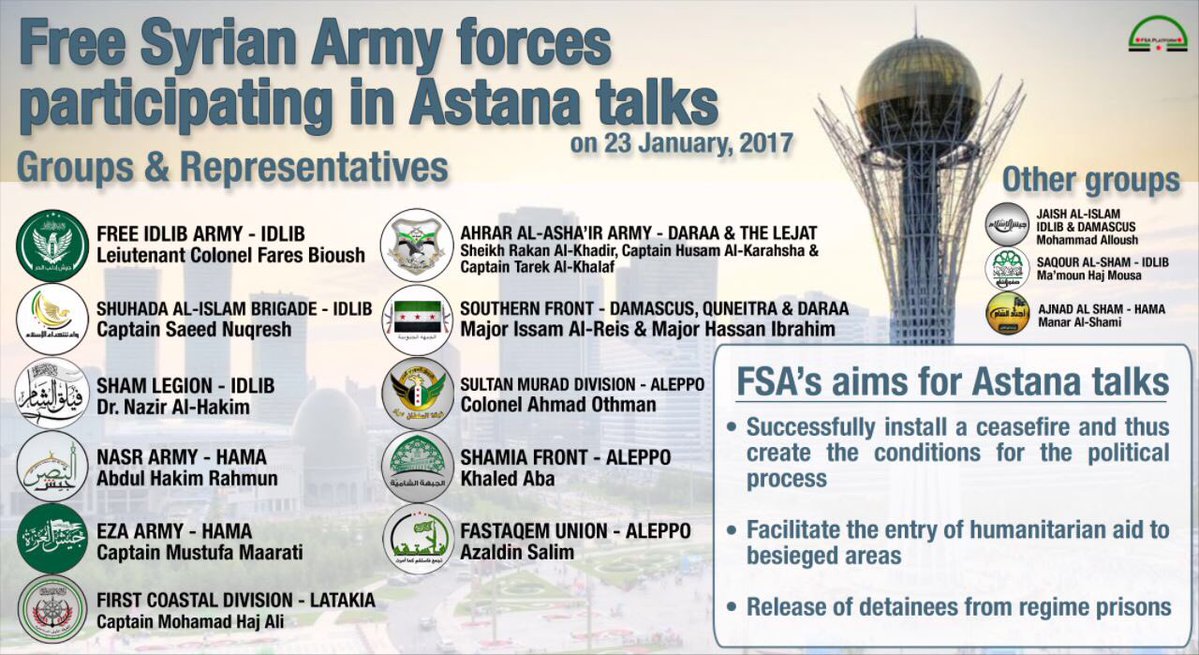

An insiders view of the Palmyra debacle on Twitter Armed opposition groups participating in the Astana Conference

Armed opposition groups participating in the Astana Conference